If you don’t hail from Canada, Michigan or a Midwestern state bordering the Great Lakes, it’s very hard to adequately envision the scope of these truly mammoth bodies of water in your mind.

The term “lake” is somewhat misleading when it comes to the Great Lakes, as most lakes are classified as water bodies that average between 5 and 200 hectares in circumference with an average depth of 42 meters (138 feet). In addition, with most lakes you can stand on one bank and see land on the other side.

Lake Superior is in a category almost all its own. To stand on its banks is to feel truly, soberingly small. To do so during a storm is to feel as though one is about to be swallowed by an angry, stormy sea, able to devour anything that touches its waters.

If you stand on a bank, you will not even come close to seeing the other side, as it’s 167 miles wide and 350 miles long. At 31,700 square miles (larger than Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire put together), and a depth of 1,332 meters (4,370 feet), it’s no wonder almost 600 (known) ships have sunk in its waters and thousands of lives have been lost.

However gargantuan and dangerous, though, Lake Superior boasts some of the most beautiful, wild, and unique ecosystems in the world.

Fish Species in Lake Superior

The diverse array of organisms found in Lake Superior includes 88 species of fish. Here we’ll cover the more common species, both those that can be fished as well as those that cannot.

The majority of Lake Superior’s 3,000 miles of rugged shoreline and its tributaries are fishable. Open-water fishing is also legal, though discretion is advised as waters can be dangerous.

1) Northern Pike (Esox lucius)

Northern pike prefer the shallow, densely vegetated banks of Lake Superior and its tributaries. They prefer waters with plenty of vegetation, or other forms of shelter from submerged logs and fallen trees. As they prefer cool waters, during the hot summer months they may move from the lake’s tributaries into the deep, cold waters of the lake itself.

Northern pike look similar to muskellunge, a fish they’re closely related to that is also fishable in Lake Superior waters. With long, lean bodies that can grow up to 3 feet long and over 15 pounds, northern pike are a highly desirable sport fish species. Their sharp, predatory teeth make them an extra challenge, as they can simply bite through most fishing lines.

A protective, slimy mucous coating over their scales also makes them difficult to handle once they’re caught, but helps deter infections, parasites, and potential predators. Studies have also found it to reduce liquid friction, meaning that pike with healthy slime coatings swim faster on average than those without. This coating combined with their slender body has earned them the charming nickname of “snot rocket.”

With incredibly sharp teeth, a slim body shape, and mottled earth-tone scales, pike have evolved to be exceptional ambush predators. They typically wait amongst thick vegetation, and dash out at passing fish, snagging them often before the other fish has any idea of what’s going on. They will also feed on frogs, snakes, rodents like muskrats, and even waterfowl.

Spawning occurs usually once per year, typically around April and May when water temperatures reach about 48° F (~ 9° C). A single female can lay between 15,000 and 75,000 eggs. These predatory fish start off feeding on tiny zooplankton in the water, then switch to small fish around two weeks of age.

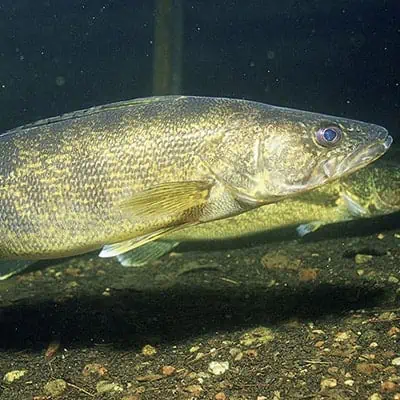

2) Walleye (Sander vitreus)

Walleye and their close relative the yellow perch can be found in Lake Superior itself as well as adjoining rivers, streams, and inland lakes. Usually they are found in waters ranging from one to ten feet in depth, as going deeper than this results in oxygen levels too low to support their needs. Due to their popularity as sport fish, their populations rely on stocking programs to keep them healthy.

The largest member of the perch family, walleye can grow to nearly 3 feet and 20 pounds. Their identification is relatively easy, with coloration of dappled brown and yellow and a distinct torpedo shape. Their eyes are large and often have a white, clouded appearance.

A spiny dorsal fin and sharp canine teeth make it known that this fish is a voracious predator, feeding on fish smaller than they are. These include bass, trout, perch, sunfishes, and even some pike.

Spawning begins once water temperatures reach between 42 and 50° F (5.5 to 10° C). A single female can lay around 100,000 eggs, typically broadcasting them over rocks that will help to catch and shelter them. They prefer dimmer, cooler waters, and after mating in shallower, warmer tributaries will typically move back to cooler Lake Superior and inland lakes.

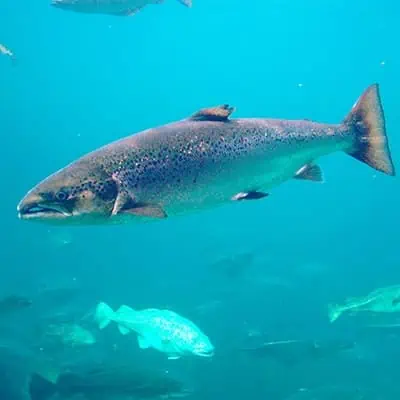

3) Rainbow Trout & Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

Four different species of trout can be found and fished in Lake Superior. These include brown trout, brook trout, rainbow trout, and lake trout. Steelheads are commonly misidentified as a fifth species, though they are, in fact, the same species as rainbows.

Rainbow trout found in Lake Superior are also known as steelhead trout, or steelheads, due to their anadromous nature. This means that they travel from the large lake up its tributary streams and rivers to spawn, but otherwise prefer the deep, cold waters of Lake Superior. Rainbows found in the shallower inland streams and lakes are simply rainbow trout, and of course have a more colorful coloration while steelheads look, well, steely.

Despite their differing appearances and habitat preferences, these two fish are genetically the same species and share a single Latin name. It’s possible that over time they will further diverge and split into two truly genetically different species, but at least for now they are one and the same.

Steelheads are capable of reaching over two feet and 15 or more pounds, while rainbow trout are considerably smaller – averaging about a foot in length and 5 or 6 pounds. Both feed on aquatic insects like caddisfly and mayfly larvae, smaller fish, snails, fish eggs, and crayfish. Spawning typically occurs in the spring once water temperatures exceed 41° F (5° C), with females laying several hundred to several thousand eggs.

4) Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush)

Lake trout prefer deep, cold waters, and are often found anywhere from 60 to 200 feet deep. They’re most active in the fall when they spawn, making this a popular time to fish for them, though ice fishing for them is also a common activity.

They are the largest of the trouts, able to reach several feet in length and over 100 pounds (though around 40 pounds is average). Their diet includes aquatic insects, crustaceans, plankton, clams, and sometimes smaller fishes.

5) Brown Trout (Salmo trutta)

Brown trout are so named for their coloration. In the cold inland streams and lakes connected to Lake Superior, they are often around a foot in length and five pounds, but those found in Lake Superior can be over two feet long and closer to twenty or thirty pounds.

They’re not picky eaters, feeding on aquatic insects, zooplankton, worms, crayfish, clams, snails, and many small fish, like minnows and darters. They often live around five years, spawning several times from October through December and laying between 400 and 2,000 eggs depending on the age and size of the female.

6) Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis)

Brook trout is the state fish of Michigan, found throughout the state’s waters. They prefer cool waters, and are readily found in Lake Superior itself as well as its connected tributaries and inland lakes.

Mature brook trout are found in deeper waters, including Lake Superior, while juvenile brook trout are more often found shallower areas like spring-fed streams, ponds, and lake banks. They often spawn from October through November, each female laying up to 5,000 eggs.

Their diet is composed primarily of insects, including mayflies and stoneflies, but they’ll also feed on worms, snails, clams, zooplankton, and other fish.

7) Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar)

Four species of salmon are found and fished in the area: Atlantic salmon, Chinook salmon, Coho salmon, and pink salmon. All Great Lakes salmon begin their lives in streams and tributaries, travel to the deeper waters of the lakes in the summer, then travel back upstream to spawn, after which they die. Some Atlantic salmon may not die after breeding, though this is uncommon. Eggs remain dormant over the winter and hatch the following spring.

Atlantic salmon can be found in shallower, warmer waters near the banks of Lake Superior during spring and fall, though they move to somewhat deeper, cooler waters once summer hits. Spawning occurs from October through December, and this is the most popular time to fish them. They grow to around 2.5 feet in length with a weight of up to 12 pounds (sometimes more). A steady diet of crustaceans, smelt, alewives (an incredibly invasive species) and other smaller fish fuel quick growth.

8) Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

Though the most popular Great Lakes for Chinooks is Lake Michigan, these hatchery stocked fish are also able to thrive in the cool, deep waters of Lake Superior that team with alewives, an important food source for the species. In the summer and early fall, they travel to inland streams and rivers to spawn.

Their average size is around 3 feet and 30 pounds, but it’s not uncommon for them to reach 5 feet and well over 100 pounds. They eat crabs, clams, and crayfish when young, and switch to feeding on other fish as adults.

9) Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch)

A very popular species, about 10,000 Coho salmon are caught in Lake Superior each year. The average Great Lakes Coho is around 5 pounds and a foot long, but they can grow up to 4 feet and 20 pounds. Spawning occurs from late September through November. Even when they travel to the lake, Cohos prefer shallower waters and are most often found at depths of five feet or less.

10) Pink Salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha)

Pink salmon are both the most stable and the smallest of the Pacific salmon species found in North America. Their typical size is about 2 feet in length and 5 pounds, but some have been found in Lake Superior that were closer to 15 pounds.

During the spawning season, they’re quite an important food item for bears, predatory birds, and scavenging wolves and coyotes. They themselves feed on small crustaceans and fish.

11) Lake Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis)

As might be surmised by their name, lake whitefish have a pale coloration. They look quite similar to their close relative the cisco, one of the primary differences being that lake whitefish’s snout overhangs its shorter lower jaw. This allows them to feed easily both on lake bottoms as well as water surfaces.

These deep dwellers are quite reclusive, often found in schools at depths of up to 200 feet. Their size averages at a foot and a half in length and up to four pounds. However, the largest whitefish ever on record was actually caught in Lake Superior, and was a whopping 42 pounds!

As juveniles, they’re found along shallow shorelines and feed on zooplankton, but as adults move to much deeper waters and feed on aquatic insects, freshwater shrimps, fish eggs, and small fish. Most adult feeding takes place at or near the bottom of the water. Their diet is somewhat restricted due to their small mouths.

Spawning occurs from September through November in shallower waters two to four meters deep, typically at night. Depending on her size, a female lake whitefish can lay anywhere from 10,000 to well over 100,000 eggs. These are dispersed over sand or rock, and hatch the following spring.

12) Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens)

If you’re looking for more of a challenge, the large lake sturgeon of Lake Superior’s numerous tributaries are legal to fish in many locations. Double check regulations for the exact area that you wish to fish, but in many areas the harvest season runs from late April to early May and early June through mid to late September. Catch and release is allowed from October through April.

All sturgeon that are fished must be a minimum length; the exact measurement differs depending on the waterway and local entity responsible for regulating fishing in that area. There is a limit of 1 sturgeon per angler per year. Both of these regulations are part of an ongoing species recovery plan.

Populations were decimated in the 1800’s by mass fishing of these large creatures, both for food and because they were viewed as pests, as they would accidentally swim into fishing nets and destroy them. The sturgeon family is considered one of the most endangered animal families in the world by the IUCN Red List, a direct result of habitat destruction, pollution, and overfishing.

The lake sturgeon of Lake Superior are the oldest and largest of the Great Lakes fish species, capable of reaching over 7 feet in length and over 200 pounds, with males living around 55 years on average and females living up to 100 years. They only mate every two years or less frequently, making it even more imperative that anglers abide by the fishing regulations for these ancient creatures.

Rather than actual scales, sturgeon possess tough skin and bony plates, remnants from their prehistoric days many millions of years ago. Despite their massive size, sturgeons are relatively harmless, using their incredibly sensitive facial barbells and flat snouts to locate bottom-dwelling prey like snails, crayfish, insect larvae, mussels, fish eggs, and clams.

13) Burbot (Lota lota)

Burbot are perhaps a lesser known fish species, but are one of the top predators in the lake. They feed quite voraciously on smelt, perch, lake trout, sticklebacks, bloater, sculpin, bass, fish eggs, clams, and crayfish and other crustaceans. Younger, smaller burbots are eaten by larger bass, smelt, lake trout, muskellunge, and sometimes yellow perch if the burbot is small enough.

Sometimes called eelpout for their long, slimy, almost eel-like appearance, burbot are able to grow up to 30 inches long and 18 pounds, though closer to 12 inches and 2 pounds is average. Their slender bodies are quite flexible; these fish have been known to wrap themselves around the arms of fishermen after being caught.

They are incredibly sensitive to pollution and turbidity, which is why they’re able to thrive in the clean, cold waters of Lake Superior. They can be found closer to the surface during the winter, but in the summer dive into deeper waters between 25 and 60 feet down.

Spawning occurs in the winter, often directly beneath the ice. This makes them a highly sought after catch among ice fishers. As many as one million eggs per female are laid in sand or gravel a few feet below the water’s surface.

14) Deepwater Sculpin (Myoxocephalus thompsoni)

Regarded as one of the weirdest Lake Superior fish, the sculpin is a small fish at only about five inches long. It’s of great ecological importance, as it feeds a variety of other organisms, including lake trout and burbot. They’re bottom feeders, eating freshwater shrimp and other crustaceans, aquatic insects, fish eggs, and small fish.

Sculpins have very wide, flattened heads, as though they’ve been stepped on. Their bodies taper to be much smaller and thinner by their tails. They’re also scaleless, instead covered by tiny, curved spines. Large pectoral fins allow them to scoot and “walk” along the sediment, and they do this quite often rather than swimming. Fanned spikes protrude from their cheeks, beneath bulbous eyes.

Despite their somewhat freaky appearance, deepwater sculpins are quite harmless, gentle creatures. They live largely in solitude along the bottom of Lake Superior, and as nocturnal creatures they much prefer these dark depths. They spawn year round at these depths, as long as temperatures are 40° F (4.4° C) or below. Females can lay up to 400 eggs per spawn period.

There are three other species of sculpin found in Lake Superior and its tributaries. The mottled sculpin is the most common, living upstream in rocky streams attached to the lake and typically reaching three to four inches in length.

The slimy sculpin is found along the lake’s shallow banks and stream headwaters. They look about the same as mottled sculpins, distinguishable by location more than appearance.

The spoonhead sculpin is the smallest of the four, averaging two inches in length and found in shallow, rocky streams where they can easily hide. All sculpins share the same scaleless, spiny, oddly-shaped body plan.

15) Kiyi (Coregonus kiyi)

Kiyi are an interesting species that are endemic only to the Great Lakes. Though they were historically found in every Great Lake except for Erie, they’ve now been extirpated due to overfishing in all but Lake Superior. Although kiyi seem to thrive in Lake Superior, they are listed as being vulnerable and of “special concern,” and therefore absolutely cannot be harvested.

They require fresh, clean, cool water, and are often found at depths ranging from 100 to nearly 700 feet. These salmonids, sometimes referred to as the big-eyed chub, average around 10 inches in size, or 25 centimeters, with large eyes that account for nearly 25% of its head’s length. These bulbous eyes enable them to literally keep an eye out for lake trout, their primary predator.

Kiyi eat plankton, aquatic insects, and minnows, but their favorite food source is mysid crustaceans. In fact, their swimming patterns are largely influenced by these crustaceans – during the night, they follow the mysids closer to the water’s surface, and at night they follow them down to the lake’s depths, hunting them with great accuracy and speed.

Spawning occurs during the winter, from November through December, with females laying eggs on gravelly substrate over 100 meters below the water’s surface and males fertilizing them after.

16) Threespine Stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus)

JaySo83 CC BY-SA

Four species of sticklebacks can be found in Lake Superior and its tributaries – the threespine stickleback, fourspine stickleback, ninespine (sometimes called tenspine) stickleback, and the brook stickleback. Of these, the ninespine and brook stickleback are native, while the threespine and fourspine stickleback are invasive.

The threespine stickleback is a two to three inch long fish with three spines atop its back to help protect it from predation. It’s an invasive species to Lake Superior, and is so aggressive despite its small size that it’s outcompeting small native fish like the yellow perch and native sticklebacks.

Most often found along the shallow banks of Lake Superior, these little guys prefer sandy bottoms. In the spring, males build rather intricate nests out of sticks, algae, and plant matter, which they attach to emergent plants. Passing females lay their eggs in this somewhat submerged nest, and afterward the male fertilizes them. Hatched juveniles are sometimes literally pushed from the nest by the father, at which point they become fully independent.

Primary food sources include midges, mosquito larvae, and zooplankton. Some birds, like kingfishers and terns, as well as larger fish like bass, may eat threespine sticklebacks.

17) Fourspine Stickleback (Apeltes quadracus)

Also an invasive species in Lake Superior, the fourspine stickleback is quite similar to the threespine. It has four very small spines on its back, which often look more like vertical fins than spines. It is thought that they, as well as threespine sticklebacks, were accidentally introduced to Lake Superior via bilge discharge from sea-faring ships.

Fourspines prefer weedy shallows, where they build nests similar to that of the threespine. Spawning also occurs in the spring, and their diet is the same as that of the threespine stickleback.

18) Ninespine Stickleback (Pungitius pungitius)

Misleadingly, this 2.5 inch long species often has anywhere from 8 to 11 spines. They can be found in Lake Superior’s weedy, shallow banks as well as well-vegetated streams and connected inland lakes. If the water is shallow and vegetated, a ninespine can probably be found there.

Just like the previously discussed sticklebacks, ninespine males also construct extravagant nests among plants, threatening juveniles to leave the nest shortly after hatching so that females will lay a new batch of eggs in it.

They feed primarily on aquatic insects like mosquito and mayfly larvae, as well as insect eggs and sometimes very small crustaceans. Most larger fish and predatory birds feed readily on ninespine sticklebacks.

19) Brook Stickleback (Culaea inconstans)

Brook sticklebacks are around 2 to 3 inches long and have anywhere from three to seven spines, though five seems to be average. As their name implies, brook sticklebacks are most often found in small brooks and streams. However, they can also sometimes be found along the shallow banks of the lake.

Despite their protective spines, brook sticklebacks are readily consumed by brook trout, large and smallmouth bass, northern pike, yellow perch, walleyes, and predatory birds like kingfishers, herons, terns, and even waterfowl such as mergansers. They themselves eat aquatic insects, snails, worms, and occasionally algae.

Just as with the other sticklebacks, brook sticklebacks spawn in the spring when waters are between 50 and 68° F (10 to 20° C), with males building their characteristic vegetation nest. Each female that visits the nest can lay up to 100 eggs, which are then fertilized by the male.

20) Splake (Salvelinus namaycush X Salvelinus fontinalis)

Splake, also known as slake or wendigo, are a genetically stable cross between a female lake trout and a male brook trout (also sometimes called speckled trout). Though initially bred in hatcheries beginning in the late 1800s, splake can be naturally occurring, as well, and are often stocked in Lake Superior by hatcheries as they are sought after by many anglers. They typically grow between 10 and 18 inches within two years, though can be larger if resources are ample. They look quite similar to brook trout and can be hard to distinguish. Look for a slightly forked tail, whereas brook trout will have a more square tail and lake trout will have a deeply forked tail. Their speckled patterning tends to not be quite as vibrant as that of brook trout, but the most telltale clue is the tail. You’re unlikely to mistake a splake for a lake trout, as splake are significantly smaller than their often massive lake trout relatives.

Interestingly, splake tend to grow more quickly than either of their parent species and often live an average of four years as opposed to just one year. Their relatively fast growth rate is likely partially behind this, limiting the ability of other, larger fish to eat them. Much like brook trout, splake feed on insects such as mayflies and caddisflies, smaller fish, worms, crustaceans, with their diet being most heavily composed of smelts, white perch, yellow perch, and minnows. One of the primary drivers in stocking these fish is to help keep the non-native smelt population in check.

As splake are not known to readily naturally reproduce (though they are genetically able to), they are typically found in locations where they are stocked by hatcheries, such as Lake Superior and its inland lakes and ponds. They are most often found closer to the surface and shorelines in spring and fall, but in the summer delve into deeper waters as they prefer temperatures below 60º F (15.5º C).